FitzGerald, Edward (trans.),

The Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám, with Twelve

Photogravures after Drawings by Gilbert James, George Routledge and Sons

Ltd., London, 1904.

Octavo;

hardcover, with gilt decorated and titled upper board and spine; 160pp., top

edge gilt, with 12 monochrome photogravure images each with a tissue guard.

Somewhat rolled; all corners bumped; boards well-rubbed with some stains; spine

is sunned, softened at the head and tail and with a woodworm hole at the foot;

free endpapers have been removed; frontispiece is detached and its tissue guard

is missing; all pages are lightly embrowned, especially at the page and text

block edges; scattered foxing throughout, especially around the plates; offset

to endpapers. Fair to good.

Far

be it for me to suggest that, after Elihu Vedder and before Edmund Dulac, no

other artist turned their hand to the Rubaiyat

and produced an illustrated version of the poem. On the contrary: once Vedder

had proposed the possibility, illustrated versions flourished, reaching a peak

in 1909 with Dulac and Willy Pogany (of whom, more later). Technology was the

time-keeper in this race however, and the production of Rubaiyat copies marched to its beat.

It’s

good to remember that Vedder’s images for his version of the poem contained the

text as an intrinsic part of the illustration: that is, the text was

hand-written onto the image so that text and image could be printed at the same

time. This was a cheap work-around past the problem that text and images could

not, at that stage, be printed concurrently. Another way around the issue was

to print the images separately and then to glue, or “tip in”, these plates onto

blank pages within the printed text block. This was done by hand and was very

time-consuming.

Many

illustrators turned their hands to productions of the poem, often simply

designing the book or providing a single frontispiece image (which brought down

production costs). Designing meant providing repeat images or patterns to be

used as endpaper decorations, margins, chapter headings or colophons (those

intricate images which signal the end of a section within a book). Designing a

book extended to the typeface and font of the text and occasionally required

large initials to be created also. Many exercises in two-colour process

printing came of these simpler, less pictorial editions. A well-designed book

gave a sense of a unified production and made the work seem more satisfying.

Which

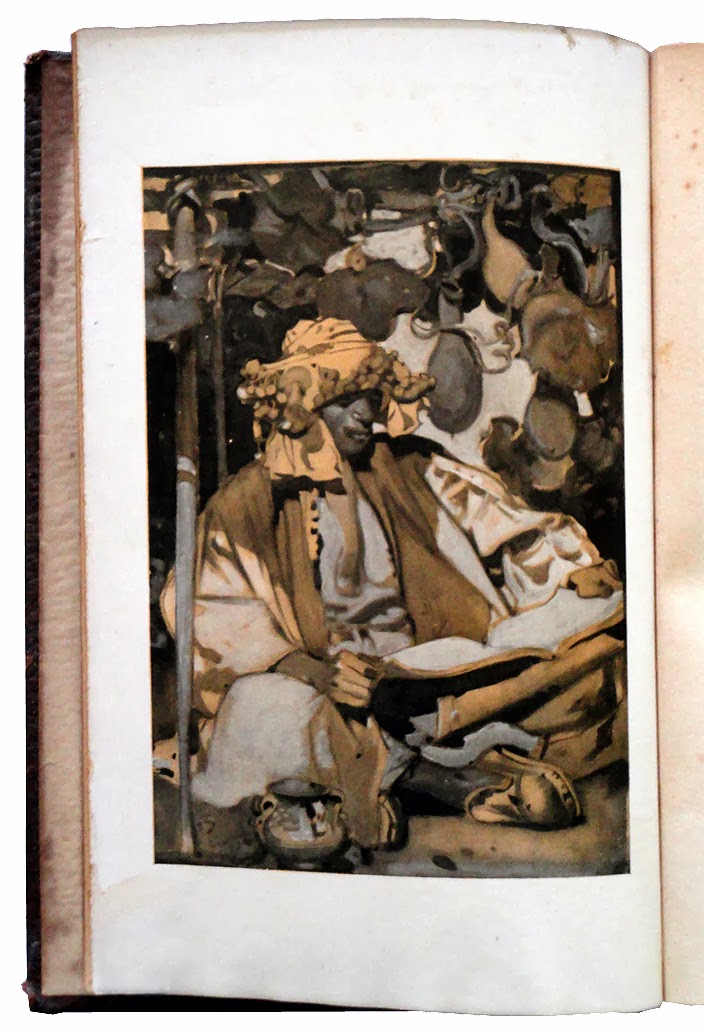

brings us to Gilbert James. James is probably the most enigmatic of the Rubaiyat illustrators, since very little

is known about him. He was (as far as can be determined) born in Liverpool and

illustrated several collections of fairy tales. Between 1896 and 1898, he

published many images inspired by the Rubaiyat

in the magazine The Sketch, for which

he worked along with several other journals. These were collected together in

one volume in 1898 by the publisher Leonard Smithers of London and sold well.

The original set of images were monochrome drawings; those images were re-used

via the photogravure process for the 1906 re-release shown above. By this time,

these new photographic processes had also been thrown into the mix of

technological innovations with which the printing world was experimenting.

In

the first decade of the Twentieth Century, Gilbert James prepared no less than

three complete sets of images for different editions of the Rubaiyat. His style sits squarely in the

Orientalist school of Rubaiyat

illustrators. Vedder’s images, no doubt informed by the Italian surroundings

amidst which he prepared them, are a Classical imagining, tinged with overtones

of the Art Nouveau: they have been called the first Art Nouveau works produced

in America. Dulac’s work too, is Orientalist in nature but is far more lavish

than the images produced by James: his drawings are far more static and sombre,

obviously informed by the more introspective and gloomy imagery of the poetry.

By that fateful year 1909, James had also moved into the world of colour and

his best known set of pictures took full advantage of the new printing

processes:

FitzGerald, Edward (trans.),

Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám, Edited, with

Introduction and Notes, by Reynold Alleyne Nicholson, A. & C. Black

Ltd., London, 1946.

Octavo;

hardcover, with decorated spine and upper board and blue titling on black

decorative labels; 136pp., with a full-colour frontispiece and 7 plates

likewise. Boards slightly fanned; retailer’s bookplate to front pastedown;

offset to endpapers; text block edges faintly spotted. Price-clipped and

over-printed dustwrapper is well-rubbed and chipped along the edges and the extremities

of the spine panel; a tipped-in note from the publisher appears on the front

flap. Good to very good.

If

anything negative can be said about James’ catalogues of Rubaiyat images, it is that he tends to recycle his imagery again

and again. Most of his pictures contain the same two figures – a poet in kaftan

and tarboosh accompanied by a saki,

or cupbearer – in various bucolic landscapes, with little or no relevance to

the verse they appear alongside. Different editions show slight re-workings of

older compositions, which suggests either time-pressure or laziness on his

part. Some images are tentative or banal; others dynamic and masterful: either

way, they are a handsome addition to the text wherever they appear.

Another

artist who contributed early to the Rubaiyat

phenomenon was Sir Frank Brangwyn. His first edition was produced by the London

company of Gibbings in 1906. Unlike Gilbert James, who remains mostly anonymous,

Brangwyn is very well known indeed, a member of the peerage and of the Royal

Academy. While my collection lacks a copy of the first Brangwyn edition, I do

have copies of two later editions.

FitzGerald, Edward (trans.),

Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám, Illustrated by

Frank Brangwyn, A.R.A., T.N. Foulis, London, 1911.

Square

octavo; hardcover, with gilt upper board and spine titling; 128pp., untrimmed

and top edge gilt, with half-tone decorations on each page with coloured

initials, and a full-colour, tipped-in frontispiece, with seven additional

plates, likewise. Very slightly rolled; boards well-rubbed with some stains and

corners bumped; spine sunned; minor scattered foxing throughout; several pages

towards the end have been roughly opened; plate number six has been folded and

one-third has come away (now missing). Else, good.

Brangwyn’s

illustrations are expressionistic and are a distinct departure from the Art

Nouveau and Symbolist leanings of Vedder and James. Nevertheless he manages to

capture an idyllic and vivacious Oriental sensibility which places him firmly

in that camp of illustrators. His almost Impressionist portrayals of light and

water lend a strong sense of place throughout his images, a place which,

arguably, owes more to countryside England than the Middle East. That being

said, his pictures ground the philosophy of the poetry in a “real” context and

steers the imagery away from the heavily choreographed formality of the Art

Nouveau.

FitzGerald, Edward (trans.),

Rubáiyát of Omar Kháyyám, Introduction by

Joseph Jacobs, designs by Frank Brangwyn, A.R.A., Sampson Low, Marston

& Company, London, n.d. (c.1932).

Octavo;

hardcover, bound in full brown morocco with gilt spine and upper-board titling

with gilt decorations, decorated endpapers; 135pp., top edge gilt printed in

green with decorations, with a full-colour tipped-in frontispiece and three

plates likewise, one bound in. Top hinge starting; previous owner’s ink inscription

to front free endpaper; spine head heavily chipped; corners bumped; offset to

endpapers; text block and page edges lightly toned; mild scattered foxing

throughout. Good.

Sir

Frank Brangwyn (1867-1956), along with Sir Edward Burne-Jones, is one of only a

handful of well-known artists who took to illustrating the Rubaiyat. Brangwyn was a regular contributor to the Royal Academy’s

exhibitions and turned his artistic attentions to furniture, pottery and work

in murals. He created two portfolios of images based upon the Rubaiyat in the early years of the Twentieth

Century most of which are taken from small works in oil. As with James’ images,

these were used again, whole and in part, across the next hundred years by a

wide variety of publishing houses.

No comments:

Post a Comment