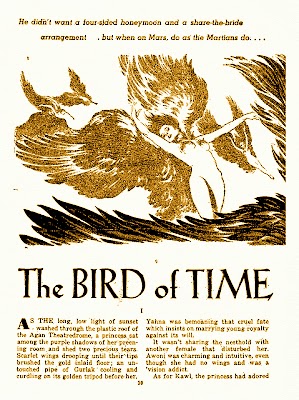

VII.

“Come, fill the Cup, and in

the Fire of Spring

The Winter Garment of

Repentance fling:

The Bird of Time has but a

little way

To

fly – and Lo! the Bird is on the Wing.”*

This

verse is one of the more memorable ones and deftly encapsulates one of the

running themes of the whole collection: namely that our time here on Earth is

finite and that it should not be wasted. We are still in the Spring section of

FitzGerald’s arrangement here and like many of these verses, the tone is

imperative and urgent, calling us to hurry up or miss out. Here also is the

notion of not wasting time on regret: guilt should not weigh us down or prevent

us from moving forward; this new re-awakening allows us to cast off our old

cares and make a new start.

FitzGerald’s

later re-workings of this verse resulted in only minor alterations: “The Winter Garment” became “Your Winter Garment” and the final line

was changed to “To flutter – and the Bird

is on the Wing”. These changes arguably made the tone less pompous and

melodramatic (“Lo!”) and the use of

the pronoun makes the impact of the verse more immediate and personal; but the

meaning is not altered in any fundamental sense. Personally, I prefer “fly” to

“flutter” – because it makes that Bird of Time seem more dramatic and capable –

but, each to their own.

This

is probably a good time to discuss the other translations which FitzGerald

undertook and the differences that appear as a result. My sense is that,

whichever version of the Rubaiyat you encounter first, that’s the version you

stay with. I read the First Translation and that’s the one that feels the most

natural to me. I find that some of the later re-workings seem a bit tortured and

less spontaneous; that’s not to say that I can’t see why FitzGerald made the

alterations, it just boils down to a matter of personal preference. Take this

for example:

“Wake! For the Sun beyond

yon Eastern height

Has chased the Session of

the Stars from Night;

And to the field of Heav’n

ascending, strikes

The

Sultan’s Turret with a Shaft of Light.”

(From the Second Edition, 1868)

“Wake! For the Sun, who

scatter’d into flight

The Stars before him from

the Field of Night,

Drives Night along with

them from Heav’n and strikes

The

Sultan’s Turret with a Shaft of Light.

(From the Third, Fourth & Fifth Editions, 1872, 1879 &

1889)

Reading

through the variations, you can see the progression of thought leading to the

point where FitzGerald was finally happy with the sense of the verse. Just

being able to do this – comparing variants towards a final polished state – is just

one of the pleasures of reading the Rubaiyat.

Personally

though, the first stabs, for me, seem the more spontaneous and instinctive. I

wonder if FitzGerald felt driven by the criticism he attracted to polish,

polish, polish. I hope not; I like to think that he fiddled around with it as a

purely pleasurable exercise and I believe that he was epicurean enough for that

to have been his sole motivation.

As

we’ve seen, the Bird of Time is a living, breathing, growing sparrow; no paralysed

eagle.

*The

British writer and poet Robert Graves didn’t like this poem. Or rather, he particularly

didn’t like Edward FitzGerald, and made a point of tearing him down and nit-picking

his efforts at every opportunity. As we shall see later, he should have left

well enough alone.

With

this stanza, Graves pointed out that it derives ultimately from a poem called “Mantiq Taiyur”, penned by another

Persian poet named Attar; FitzGerald had previously translated this verse under

the title “The Bird Parliament”.

Regardless of the source, the sentiment expressed here ties in with and

supports Omar’s central theme; and since this is a free translation anyway, who

really cares if FitzGerald took a little inspiration on the side?

No comments:

Post a Comment