XVI.

“Think, in this batter’d

Caravanserai

Whose Doorways are

alternate Night and Day,

How Sultán after Sultán

with his Pomp

Abode

his Hour or two, and went his way.”

This is a neat little image: a caravanserai is basically a semi-permanent encampment of traders, their tents arranged in an orderly fashion around a central meeting area. These locales were designed as places where traders and travellers could meet to discuss the market, swap gossip, and rest secure knowing that there was some degree of safety in numbers on the road. You can easily imagine such a campsite settling down in the evening: a cluster of little tents each with its lamp and a patch of growing darkness between each one – effectively an “alternate Night and Day”.

FitzGerald

devises many ways in which to encapsulate this idea of endless, successive days

and nights, to symbolise the progress of time. We’ve seen the Bird of Time on

the wing already and this is yet another urging to be aware that time is

endless and that our participation in its passage is woefully short.

Have

you ever wandered into a place that reeked of history? Have you ever sat down

somewhere and been compelled to say “if only these walls could talk?” Well,

what they’d speak of is how some “Sultán after Sultán with his pomp” stayed

here for a little while and then moved on. There are restaurants and bars in

Paris where tables bear plaques to indicate that this was where Gustave

Flaubert sat, or that Alexandre Dumas took his coffee here: in this sense,

FitzGerald is saying once more that we need to leave an impression; we need to

make our mark. In one sense this is an exhortation to do something useful with

the time we have. To be remembered as a Sultán and not a Slave.

There

is a flipside to this, and this is the other recurring theme of FitzGerald’s

work: whether a Sultán or a Slave, no-one is immune to the harsh governance of

Time. Wealth and consequence doesn’t make you immune to Death. Time will get

you in the end.

The

closest we get, is to enjoy the batter’d caravanserai. When everyone else has

moved on, the place remains. We get to absorb the traces of those who went

before, to learn the lessons that they have left behind. This is the value of

age, and of the old. This is the lesson of place.

When

we denigrate the things that those before us have built, we deny our own past –

we dismiss the lessons to be learned, the message that is Time. Santayana said

it and it’s become cliché nowadays – “those

who forget the past are doomed to repeat it.”

We

are what we achieve in our lives. But we are also what led to us being here. If

we claim to have sprung wholly from the Now, untrammelled by the things that

went before us, then we are, in effect, simply striding out of the encampment

and into the dark desert beyond, a desert that is filled with jackals and

scorpions and a lonely, isolated death.

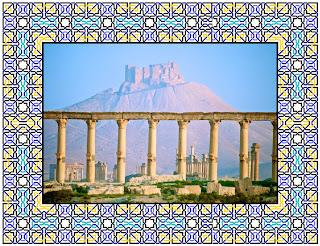

Call

it a caravanserai; call it Nineveh; call it Palmyra; call it the Pyramids of

Giza. No-one came here of their own accord and no-one is free from the debt

they owe the past. FitzGerald knew this; he saw it in the verse and he let us

know that Omar knew it too.

No comments:

Post a Comment