XIII.

Look to the Rose that blows

about us – “Lo,

Laughing,” she says, “into

the World I blow:

At once the silken Tassel

of my Purse

Tear,

and its Treasure on the Garden throw.”

At

this point we encounter our second reference to a Rose in the poem and, for the

second instance, also find a word that, over time, has fallen from common use,

making understanding somewhat tricky. Since, in this verse, they occur

together, it seems ideal to attack them both at once.

Firstly,

the Rose is a standard image of Sufi iconography. Like many such images, it

relates back to the idea of God and is an oft-used symbol of the Deity. Due to

their range of colour and intense perfume, and given that they were quite

difficult to grow and maintain throughout many water-poor Islamic regions, roses

were much sought-after. Sufi adherents equated their heady aroma with the intensity

of Divine inspiration and their thorns became symbols of the difficulty in

attaining such a union with God.

Islamic

art, denied the possibility of creating the likenesses of living beings or

naturally-occurring phenomena, devoted itself to the creation of patterns,

usually geometric forms of an intricate nature. Roses, in that they present a

circular repeating pattern from the inner stamen to the outer petals, were a natural

inspiration for many designs, from rugs, to wall or floor mosaics, to windows.

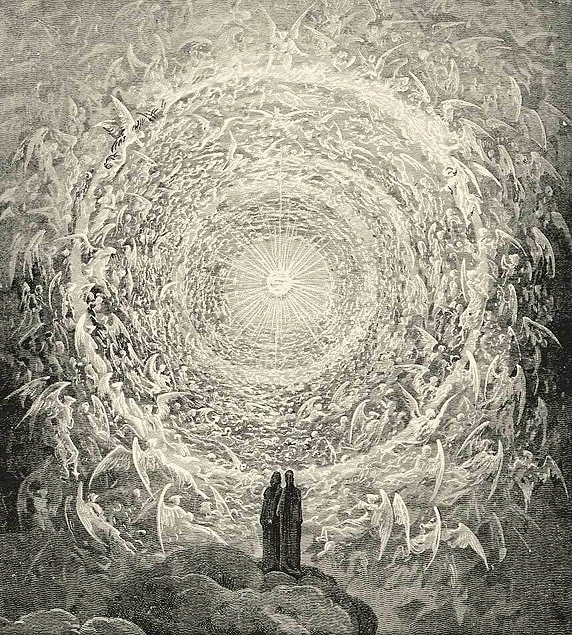

A

common notion in spiritual art is the dissolution of matter into the spiritual.

In Western cathedrals, the great stained windows (called, incidentally, “rose

windows”) seek to dissolve the heavy masonry of the sacred enclosure by bathing

the walls in coloured light; in the Islamic world, a similar effect was attained,

but by means of patterning the walls in paint, cloth, or tiles.

As

the Islamics exulted over the perfection of the rose, so too did the

philosophers of the West. In Western thought from the earliest times, the world

was considered to be arranged in hierarchies, or tiers of rank, creating an

ordered universe. Plants and animals were listed from the “lowest” to the “highest”

in terms of certain qualities equating to notions of virtue. This simplistic

attempt at rationalising the universe remains with us: even today, we refer to the

Lion as the “king of beasts”, and the Eagle as the “king of birds”; so too, is

the Rose considered the “king of flowers”.

(Interestingly,

this notion of a Universe ranked into order is also a mainstay of Confucian

thought, the earliest state-sanctioned religion of China, pre-dating Western philosophy

by several millennia. It seems that no matter how separate from each other we

think we are, there are always fundamental ways in which we have common ground.)

With

the symbolism of the rose firmly in mind, let’s turn to that word which

nowadays causes some headaches. That word is “blow”.

In

the language of FitzGerald’s day, flowers “blew” all the time. It doesn’t mean

that they were tossed by the wind; rather it refers to them bursting open, or

blooming. There’s an extra sense to the word in this context, referring to a flower

as being just past the point of perfection; to be on its way out. From this

sense, we get other expressions, such as “blowzy”, meaning to be colourfully

dissipated, and of course “overblown” to mean decadently showy, or over-ripe.

In

a sense, FitzGerald (possibly working from a notion only implied by Omar) seems

not to be talking about the Rose as a symbol of perfection, but rather as an “everyman”

cipher, referencing each individual’s potential rather than appearance. He

seems to be saying that every person comes into their own and leaves behind

something upon which future generations build. The “Treasure” of the Rose is

the seeds of the future, stored in the “Purse” of the flower’s rosehips. FitzGerald

devoted most of his life to the growing of flowers, so a botanical metaphor

wouldn’t have been much of a stretch for him.

Here

again is the idea that there is a finite amount of time for each of us, but

coupled with it is the notion that everyone has the potential to create the

future, to add something to the “Garden” of creation. That Bird of Time is

still relentlessly flapping onwards and time, it seems now, is not the only

thing that can be wasted.

Roses,

in fact, caused Omar quite a bit of trouble as it turned out, and we’ll get

into that further when we hit ruba’i

67; suffice it to say that he placed some value upon being buried by a rose

garden when he died. Religious hardliners hunted him most of his life for this obscure

reason (among others); nevertheless, roses do

bow over his grave in Iran today, and cuttings from those same rosebushes were

taken from Persia and planted over FitzGerald’s grave in England.

It’s

a fitting symbol of unification and the fostering of peace if ever there was

one. Just like the poem itself.

No comments:

Post a Comment