FITZGERALD,

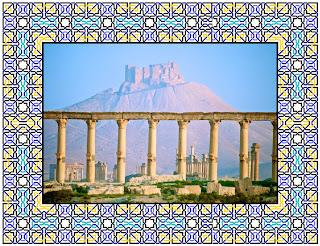

Edward (Arthur Szyk, illus.), Rubáiyát of

Omar Khayyám, rendered into English verse, The Heritage Press for the

George Macy Companies Inc., New York, NY, USA, 1946.

Quarto; hardcover, quarter-bound in

illustrated boards; unpaginated (24pp.), printed and bound orihon style, with a full-colour, gilt-decorated frontispiece and 7 plates

likewise. Boards rubbed with mild bumping; spine extremities softened; mild

spotting to the text block edges and endpapers. Lacks dustwrapper. Very good.

“Art is not my aim, it is my means.”

-Arthur Szyk.

Arthur Szyk, like Willy Pogany, was

born in Eastern Europe and, unlike many other illustrators, seemed fated to

make a living in that profession from his earliest days. Unlike Pogany,

however, who was mostly easy-going and positive, Szyk was contentious,

darkly-humoured and, with a pencil in his hand, downright antagonistic.

Born in Łódź, Poland, on the 16th

day of June 1894, Szyk (pronounced “Shick”) was the son of wealthy textile

merchants, of Jewish extraction but non-Orthodox. Throughout his life, Szyk was

proud of his heritage, both national and religious, and used his skills to

promote pro-Polish causes and to fight anti-Semitism wherever he found them.

During the Łódź Insurrection in 1905,

Szyk’s father lost his eyesight when a disgruntled worker flung acid in his

face. Despite this, Solomon Szyk staunchly supported his son’s artistic

leanings, sending him to the Académie Julian in Paris for his education.

There, Arthur was exposed to all the

great artistic movements which arose during the start of last century. However,

it seemed that the more he encountered the New in terms of art, the more he

chose to cleave to the traditional, Eastern-influenced styles of his homeland,

as well as developing a liking for the stylistic forms of medieval manuscripts.

From 1912-1914, he was regularly published in the Łódź magazine “Śmiech” (“Laughter”), providing many

politically-charged cartoons and caricatures. By this time he had left Paris

and had taken up studies at the Jan Matejko Academy of Fine Arts in Kraków

studying under Teodor Axentowicz. In 1914 he went to Palestine with several

associates to observe the efforts of jewish settlers in constructing a Jewish

state; however, the trip was cut short due to the outbreak of World War One. Palestine was in the

control of the Ottoman Empire and Szyk, being Polish, was considered Russian and

therefore unwelcome in Ottoman territories.

Returning home to Łódź, Szyk was

conscripted into the Russian army and fought in the battle to defend his

hometown in November/December 1914. Whilst in the army he drew many images of

Russian soldiers which were sold successfully as postcards. At the commencement

of 1915, he fled the army and returned to Łódź, where he waited out the War. In

September of 1916, he met and married Julia Likerman, with whom he had two

children, George in 1917 and Alexandra in 1922.

Poland regained its independence from

Russia in 1918. In response to the German

Revolution of 1918-19, he illustrated a satirical work, co-authored by

himself and poet Julian Tuwim, entitled Rewolucja

w Niemczech (Revolution in Germany).

The book poked fun at the German people for requiring the permission of their

Kaiser to enact a revolutionary proceedings. Shortly afterwards, Szyk was back

in battle himself in the Soviet-Polish

War of 1919-20, which he began by working as a propagandist, and then as a

Polish cavalry officer. In 1921, he re-located to Paris once more.

In France, Szyk began illustrating in

earnest. Previous to this period, his work was mainly executed in black and

white; now he began to prefer colour and his book illustrations took on the jewel-like

aspect which became characteristic of his style. While based in Paris, he

travelled extensively returning frequently to Łódź. In Marrakesh he drew the

portrait of the Pasha, and he went to Geneva to illustrate the Statute of the League of Nations. For

the Pasha’s portrait he received the Ordre

des Palmes Académiques, for being a goodwill ambassador; he left the Statute incomplete, turning in disgust

from what he perceived to be half-hearted efforts by the League.

Also during this period, he began

illustrating the Statute of Kalisz, a

charter of liberties which were granted to the Jews by Boleslaw the Pious, the

Duke of Kalisz,

in 1264. Work on the project gained widespread recognition and, before it was

even finished, postcard reproductions of certain pages and a travelling

exhibition cemented Szyk’s popularity in the lead-up to the publishing of the

work in Munich in 1932. He was awarded the Polish Gold Cross of Merit for his

effort in showcasing the Jewish contributions made to Polish culture.

At the same time, Szyk was embarked

upon illustrating a history of George Washington and the American Revolutionary War entitled Washington and his Times. This series of 38 watercolour images was begun

in Paris in 1930 and was exhibited in 1934 at the Library of Congress in

Washington, at which time Szyk was awarded the George Washington Bicentennial

Medal.

Starting in 1932, Szyk began to

illustrate a version of the Jewish text The

Haggadah, which contained 48 full-colour illustrations and many other

decorations. It is considered to be his magnum

opus. With the unsettling reverberations which were coming out of Germany

however, Szyk was compelled to add many modern flourishes to the work – evil

characters in the work depicted in German clothing and with Hitler moustaches,

caricatures of Joseph Goebbels and Hermann Göring, and many images of

swastika-bearing snakes proliferated. In 1937 while in London, Szyk was forced

by his publishers to amend these details before the work went to print: at the

time the British Government was actively pursuing a policy of appeasement with

Germany and didn’t want anything to sour the deal. Three years of compromise

later, Szyk dedicated the book to King George VI and walked away from it. The Times review of the final work

declared it “worthy to be placed among the most beautiful of books that the

hand of man has ever produced”.

Probably compelled by the compromises

he made to this work, Szyk held an exhibition of 72 caricatures held at the

London Fine Art Society, entitled War and

“Kultur” in Poland. A reviewer in The

Times rated the display in 1940 as follows:

“There are three leading motives in the

exhibition: the brutality of the Germans – and the more primitive savagery of

the Russians, the heroism of the Poles, and the suffering of the Jews. The

cumulative effect of the exhibition is immensely powerful because nothing in it

appears to be a hasty judgment, but part of the unrelenting pursuit of an evil

so firmly grasped that it can be dwelt upon with artistic satisfaction.”

Shortly thereafter, Szyk left England

to travel to America, charged by the Polish government in exile to spread the

word in the US about the fate of Poland and the Jews under Nazi rule.

Szyk felt a spiritual affinity with the

United States and declared that he felt completely free to speak his mind

(through his art). He was inspired by various governmental proclamations and

pieces of legislation to illustrate these and to create works of art to

celebrate them. He designed stamps and official documents, but primarily he

created illustrations propagandizing the Axis powers and celebrating Allied

victories. These were published in various magazines and turned into posters

which, it is said, were even more popular amongst the US troops than their

pin-up girls. Eleanor Roosevelt said of Szyk, “This is a personal war of Szyk

against Hitler, and I do not think that Mr. Szyk will lose this war!”

Szyk’s unwavering moral compass was not

reserved only for the Axis enemies. He also created many works critical of the

American culture, particularly the entrenched racism that he perceived there. In

one cartoon he has two US soldiers – one white and one black – discussing what

they would have done with him if they had captured Hitler. The black soldier

says “I would have made him a Negro and dropped him somewhere in the U.S.A.”

The Ku Klux Klan were another hated organisation who felt his acerbic barbs.

Szyk’s popularity waned after the War

and he eventually died of a heart attack in New Canaan in September 1951. He

left behind an incredible legacy of illustrative work, not only of his war

propaganda but also many meticulously designed books, immediately recognisable

due to his minute, jewel-like work. Recent exhibitions have revived interest in

his work and re-established him as one of the most driven and passionate

illustrators of the Twentieth Century. After his death Judge Simon H. Rifkind

summed up his life with this eulogy:

"The Arthur Szyk whom the world

knows, the Arthur Szyk of the wondrous color, and of the beautiful design, that

Arthur Szyk whom the world mourns today—he is indeed not dead at all. How can

he be when the Arthur Szyk who is known to mankind lives and is immortal and

will remain immortal as long as the love of truth and beauty prevails among

mankind?”