XVII

“They say the Lion and the

Lizard keep

The Courts where Jamshýd

gloried and drank deep;

And Bahrám, that great

Hunter – the Wild Ass

Stamps

o’er his Head, and he lies fast asleep.”

There’s

been quite a lot in the news lately about lions, so I figured this was a good

time to contribute my two-cent’s worth.

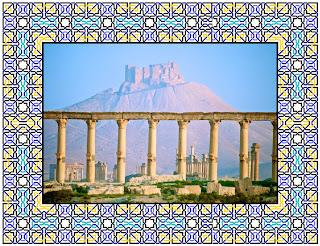

What

is this stanza saying? Essentially, it’s reinforcing previous rubai’s by saying that the works of

individual humans are short-lived and impermanent. Jamshýd was a legendary

ruler of yore to the Persians and created many great works, including a famous

cup which was referenced in stanza 5. He built magnificent palaces and

entertained lavishly in them. Now he’s dead and his castles are all in ruins.

FitzGerald

is playing the Romantic card with this verse. Not the melodramatic, treacly,

Hallmark-card of Romance, but the Nineteenth Century aesthetic movement one,

which cleaved to all things natural – after the teachings of Ruskin (who,

ironically, couldn’t cope with “natural” when he saw it) - especially the

wilder, moodier, gloomier side of the Old Dame.

“Nature

is eternal”, say the Romantics; “after we are gone, only nature will remain to

erase all our achievements”. That was all well and good, back in the day, but

now, humanity has all kinds of methods to ensure that, once we’re done with the

planet and our time upon it, Mother Nature is not going to be a sure bet to

lift herself off the canvas. Lions are an ever-diminishing quantity and Lizards

are being out-gunned by climate change.

Bahrám,

the other guy mentioned in this verse, was a famous hunter in ancient Iran, and

the “Wild Ass”, or Onager, was his quarry of choice. In his time, being a

hunter of high repute was something that could be called employment, and it was

seriously dangerous: arrows, swords, and spears really levelled the playing

field between all parties in those days, making the contest decidedly more

equal. If it were possible for Bahrám to run into a certain American Dentist of

ill-fame, I’m sure he would have a few things to say about his technique, like

hunting actual, wild, undomesticated lions, without hi-tech, laser-sighted

bows, and without guys in train carrying high-powered rifles to pull your fat

out of the fire when you screw up. Not that I’m lauding any kind of hunter; let me be clear: nowadays, the Onager is

extinct in Europe and Asia, and certainly Mr. Bahrám had a hand in that.

Unfortunately, we live at a time when anything natural that isn’t being

passively destroyed en-masse by our

mere presence, is being actively slaughtered by testosteronal A-holes with

performance issues to address. If only these morons would be content with

watching DVDs of bikini-clad women shooting automatic weaponry in quarry pits,

it would be okay; but no, they have to get out there and have a go themselves.

Here’s

a thought, especially since it’s a Shark Year, that cyclical time when sharks

roam further afield than usual and folks in Byron Bay and Perth forget that it

happens every 4-5 years, get all twitchy and start talking about “culls” and

“netting”: round up all the “he-man” hunters out there and dump them in the

oceans with a steak knife each. Problem solved.

There

are two copies of the Rubaiyat from

which I’ve drawn images for this post: the first is illustrated by Robert

Stewart Sherriffs, whose set of illustrations is one of my favourites; the

other is taken from Margaret Caird’s set of pictures and is taken from an

octavo Collins copy of the poem – usually, I come across the duodecimo version with

a single image used as a frontispiece, so obtaining this volume was a definite

bonus.

FitzGerald, Edward (G.F.

Maine, Ed.; Robert Stewart Sherriffs, illus.), Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám,

Rendered into English verse with an Introduction by Laurence Housman,

Collins Clear-Type Press, London, 1947.

Quarto;

full royal-blue leather, with gilt spine and upper board titles and decorations

on red labels, and a royal blue ribbon; 222pp., all edges gilt, with a

full-colour frontispiece and 11 plates likewise. Some sunning to the board

edges and spine; chipping to the leather at the spine head; retailer’s

bookplate to the front pastedown; mild scattered foxing to the preliminaries;

corners bumped with some minor fraying. Very good.

FitzGerald, Edward (Margaret Caird, illus.), Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám,

Rendered into English verse with an Introduction by Laurence Housman,

Collins Clear-Type Press, London, nd. (c.1920s).

Octavo;

hardcover in decorated cloth, with decorative endpapers; 56pp., with a

monochrome frontispiece and four plates likewise. Mild sunning to the board

edges and spine; spine lightly cracked; softening to the spine extremities;

some mild toning to the text block edges. Lacks dustwrapper. Very good.