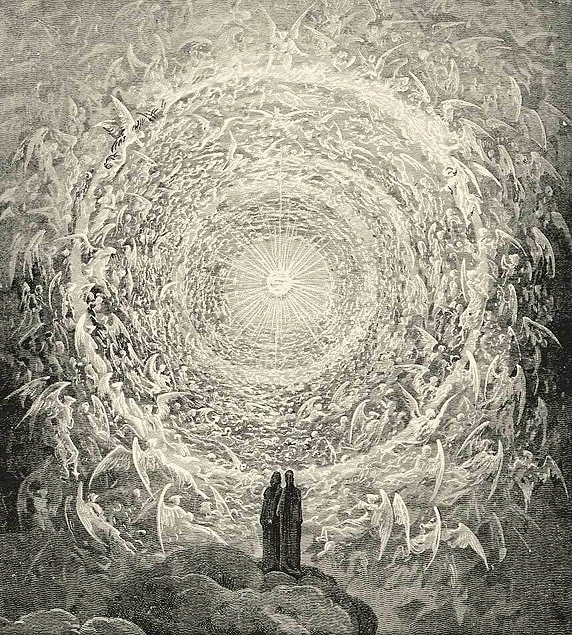

ROTHENSTEIN, Jerome, Sketch of Rabindranath Tagore, 1912.

347mm x 257mm; pencil on buff

paper stock, signed and dated by the artist; inscribed in ink with a dedication

to Danish publisher Povl Branner by Rabindranath Tagore, May 23rd 1921; original wooden frame.

The

story of Omar Khayyam and Edward FitzGerald is not unusual by any means; the

tale of the visionary Easterner championed by the lettered Westerner has many historical

precedents. Most put it down to the fascination which the East has for those of

Occidental origins – Edward W. Said wrote all about it in his groundbreaking work Orientalism (1978).

The

essence of the concept is that jaded Western palates find excitement and a

certain frisson in what they perceive

to be the licence and exoticism of the Orient; the East becomes a fantastic

playground, filled with possibilities rendered incapable of fulfilment in the

prosaic, workaday paradigm of Western culture. Whether or not such decadence and

extravagance is the actual daily reality of Eastern individuals is rendered

moot: the Orientalist ideal is a fantasy projected upon a foreign culture by

those dwelling outside of its compass.

In

no small part does this explain the fascination that the Rubaiyat has for many readers in the English-speaking world: the

poem abounds with Eastern imagery and references. It also seems to espouse

radical values, and to place those values – exciting and revolutionary as they

seem – within the Oriental context. I question however, whether the sentiments

credited to Omar and synthesised through the pen of FitzGerald, have made that

journey entirely intact.

It’s

easy to forget that Edward FitzGerald laid a heavy hand upon the quatrains

penned by Khayyam; he re-wrote them quite loosely into the English idiom and he

re-arranged them in an order that satisfied his aesthetic demands. It’s not

entirely unreasonable to credit FitzGerald’s detractors with some degree of

correctness when they say that his translation was imprecise. Even I recognise

the dangers of taking Omar Khayyam at face value through the medium of Edward

FitzGerald: in my case, it’s just that I prefer

his version before all the others.

Still,

the Orientalist sensibilities of the reader is mostly what draws them to this

work. It’s no stretch of the imagination to grasp that that is what the

Pre-Raphaelites took from it; or that it was the hook which snared the

succeeding generations of Aesthetes, Symbolists, Decadents and other artists of

the fin de siecle period of new

century enthusiasm. It’s not hard to see how the poem’s carpe diem sentiments set fires among the hearts of the

between-Wars survivors and jaded seekers after a new society: the mad

iconoclasm of the Twenties and Thirties, with its desperate flailing around to

find something of meaning and purpose to cling to, could latch onto many things

but few better than FitzGerald’s truisms.

But,

to reiterate, I can’t help but feel that most of the values expressed in the

poem are FitzGerald’s and not, strictly speaking, Omar’s.

As

an example of what I’m getting at, I’d like to turn to another Easterner whose

vision and artistry forged inroads into the West. Rabindranath Tagore was the

polymathic scion of a family blessed with equally-talented individuals, who

almost single-handedly revived and energised the literary efforts of his

homeland in Bengal. Born to a high-caste Hindu family, he was knighted by King

George V and became the first non-Westerner to win a Nobel Prize for literature;

he counted amongst his acquaintance Albert Einstein, Mahatma Ghandi and W.B.

Yeats, who was instrumental in translating his poetry into English. His

best-known work (in English translation) is entitled “Gitanjali” (1913) which was dedicated to William Rothenstein and

is a collection of his spiritual poetry:

“When thou commandest me to

sing it seems that my heart would break with pride; and I look to thy face, and

tears come to my eyes.

All that is harsh and

dissonant in my life melts into one sweet harmony – and my adoration spreads

wings like a glad bird on its flight across the sea.

I know thou takest pleasure

in my singing. I know that only as a singer I come before thy presence.

I touch by the edge of the

far spreading wing of my song thy feet which I could never aspire to reach.

Drunk with joy of singing I

forget myself and call thee friend who art my lord.”

Reading

about Tagore is quite a different

experience to reading his writing (in translation as it is). Many commentators

- Yeats amongst them, despite his complete absence of skill with the Bengali

tongue - talk of the shimmering quality of his language, and the ecstatic

fireworks of his written expression. For me, I find the poetry rather dull and

somewhat trite. This is partly because I’m instinctively wary of ecstatic verse

– I follow Confucius’ line of argument: “believe in the gods, but keep them at

arm’s length”. Secondly, being told that the translation doesn’t do the

original justice seems to be a pointless comment: it’s kind of like a “heads-up”

before the fact that the writing is going to be bad, with the caveat that I’ll just have to take their

word that for it that it’s worthwhile and go along with it. Can’t win; don’t

try. I’m being asked to take on faith something I can’t test for myself. And

perhaps there’s a bridge they want to sell me, too.

(This

is not to say that Tagore’s writing is bad; it’s just not for me. There are

some wonderful allusions and turns of phrase here; it’s just not my particular

cup of tea.)

This

probably sounds terribly cynical but there is a point: Tagore was alive and

able to oversee the translation of his own poetry from the original Bengali;

Omar Khayyam was not in so enviable a position. I’m pretty sure that Tagore’s

writing is telling me exactly what he wanted it to tell me (as far as English

can be bent into that shape); I’m fairly convinced that Omar’s poem is telling

me largely what FitzGerald wanted it

to tell me. On that basis, I’ll go with FitzGerald.

I

didn’t just throw the word “cynical” in there on a whim. FitzGerald’s take on

Khayyam has a jaded edge to it and I’m fairly sure (Robert Graves would back me

on this point) Omar never intended his poems to be read in that way. Sad to

say, I suspect that Omar’s quatrains would probably come across more like

something written by Tagore if I could read them in the original language. The

essential reality of all this is as follows:

FitzGerald’s

translation is an Orientalist fantasy; it’s a Western vision dressed up in

Persian costume to appeal to Occidental readers. Sure, it’s based on Omar Khayyam’s

verses, and sure, those verses and Omar’s reputation in Iran are secure; it’s

just that they read a little differently depending upon which side of the line

you’re sitting.

Before

we get to the end of this roller-coaster, there will be other Orientalist

writings which we’ll be looking at for comparison purposes; some of those fall

into the Orientalist camp and others don’t, but it’s always wise to keep

notions of this distorting lens in mind when looking at these types of writings.